Cities of the Dead: A Tale of Egypt’s Living Necropolis

architecture cairo history Egypt History Mamluk Architecture

Safy Allam

Image via website

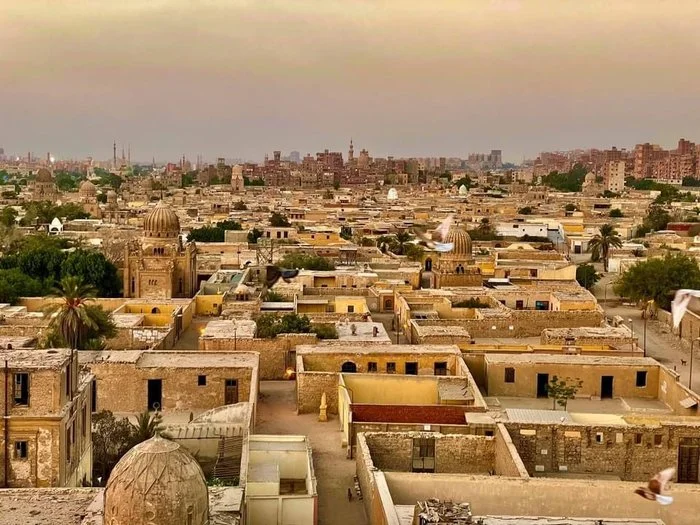

Cairo’s “City of the Dead” is unlike most cemeteries. Spread across the eastern edge of the city, it feels less like a burial ground and more like a neighbourhood. Here, tombs stand alongside courtyards, domes rise above narrow lanes, and families have made homes among mausoleums for generations.

This unusual blend of life and death is not new. For thousands of years, Egyptians have built for their departed as carefully as for the living. From the pyramids of ancient kings to the domed mausoleums of sultans, the country’s cemeteries have always carried the imprint of architecture, turning them into places that resemble cities in their own right.

Ancient Egypt – Mastabas and Pyramids

Image via website

The story begins thousands of years ago, long before Cairo was founded. In ancient Egypt, the dead were never left with simple graves. They were given homes and offered everything they might need beyond this world. Families placed food, jewellery, and treasured personal items beside the body to support the soul in the afterlife.

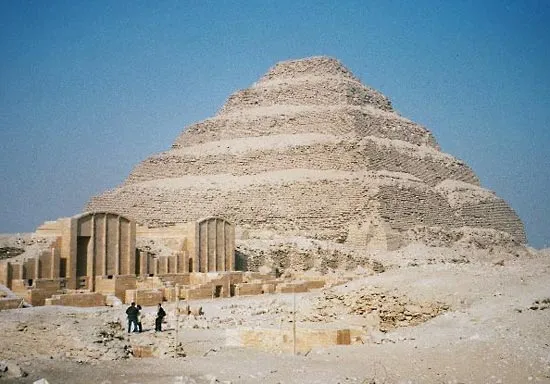

Architecture mirrored that belief. The mastabas of the Early Dynastic period were built like houses, complete with offering rooms and a false door through which the deceased’s spirit could receive sustenance. The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara rose skyward as a stairway to eternity, surrounded by temples, courtyards, and ritual halls, arranged as if forming a miniature city.

Then came the sprawling pyramid complexes of Giza: vast funerary landscapes where tombs, temples, and causeways created entire environments designed for eternity. In all cases, the architecture offered a sense of home, both in death and beyond.

Ayyubid Cairo – The Birth of Mausoleums

Image via website

Centuries later, with Fustat and later Cairo growing along the Nile, another city of the dead took shape on the desert’s edge. Legendary scholar Imam al-Shafi‘i was buried there in the early 9th century. In the 12th century, the Ayyubid Sultan Salah ad-Din erected a tomb-shrine, known as a turbah, and a madrasa around his grave, marking the first monumental structure in Cairo’s necropolis.

A few decades later, in 1211, Sultan al-Kamil built a dome over the site, creating a proper mausoleum. In later periods, Mamluks like Sultan Qaytbay added muqarnas, marble inlays, and ornate decoration. These monuments reflected the Islamic tradition of honouring scholars and saints, where architecture became both a tribute to the deceased and a space for the living to gather, pray, and learn.

Mamluk Period – Domes and Funerary Complexes

Image via website

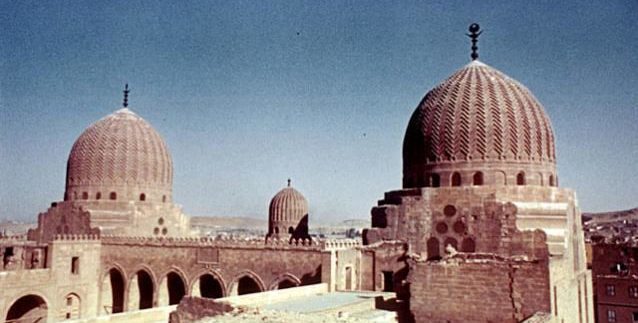

The necropolis flourished in the Mamluk era as sultans and emirs sought to immortalise their legacies in stone. These were not mere tombs; they were multifunctional complexes combining mausoleums, mosques, madrasas, khanqahs (Sufi lodges), and charitable institutions. Their design conveyed both spiritual prominence and civic ambition.

The Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq (1400–1411) includes a mosque, mausoleum, and lodging, crowned by three domes and two minarets. A few decades later, Sultan Qaytbay’s funerary complex (1470–1474) blended a mosque, mausoleum, sabil (public water fountain), and school, its lofty domes and minaret showcasing late Mamluk architectural brilliance.

Here, faith took form. The charitable endowments (waqf) ensured these buildings served the living as much as they honoured the dead, embodying the Islamic vision of continuity between worlds.

Ottoman & Muhammad Ali Era – Palatial Mausoleums

Image via website

Next, architectural styles blended into new forms. The Ottoman period continued the tradition of domed mausoleums, while the early 19th century saw the emergence of refined, palace-like tombs.

The Hosh al-Basha, built around 1854 for the family of Muhammad Ali Pasha near Imam al-Shafi‘i’s tomb, blended Ottoman and Baroque aesthetics with Islamic tradition. Lavish and dignified, it reflected how rulers saw the necropolis not only as a burial site but also as a statement of power, piety, and dynasty.

20th–21st Century – A Living but Fragile Cemetery

Image via website

These grand structures naturally became homes as well as tombs. Courtyards, rooms, and water facilities made it easy for caretakers and migrants to settle among the domes. Today, many still dwell here, some as guardians of family tombs, others drawn by circumstance, living on ancestral grounds, or simply finding shelter where they could.

Yet, Cairo’s cityscape is changing. New highways have sliced through the necropolis, and unprotected mausoleums have been demolished. At the same time, select restoration efforts, such as the conservation of the Imam al-Shafi‘i Mausoleum, highlight ongoing attempts to preserve this living museum.

To walk in Cairo’s City of the Dead is to walk through history itself, a city where every stone whispers of lives once lived, and where the dead still dwell in houses as grand as the living.

recommended

Arts & Culture

Arts & Culture

5 Book Clubs Around Cairo: Reading as a Communal Activity

Bibliothek Egypt Cairo Book Clubs +5 Beverages

Beverages