-

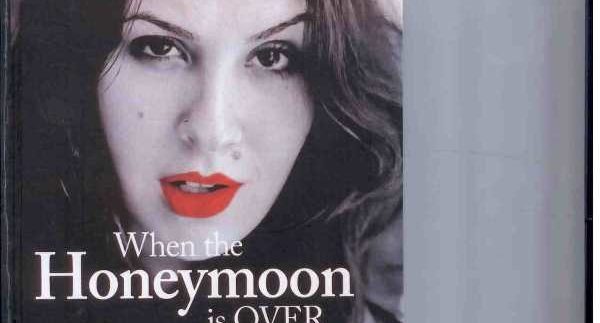

May Taher

-

Fiction

-

Out now

-

English English

-

110 EGP

-

Various

Soraya Morayef

With a slew of

young, Egyptian female authors publishing their works of fiction in the last two years,

May Taher is the latest to debut on the local market with When the Honeymoon is Over; a collection of sixteen short stories

about Egyptian couples and the tumultuous nature of relationships.

The

collection covers the same old stories you’ve probably heard about: the husband

who cheats, the successful single woman who returns to Egypt to get married (she’s in her

early thirties-the horror!), the recently divorced single mother trying to date

again, the wife who’s had enough of her overbearing mother-in-law and slob of a

husband… It’s the familiarity of the characters and their stories that will help

this book appeal to a large Egyptian audience, especially young women in

relationships.

Though these stories could easily happen to someone you know, they lack the depth and realism to

make them believable. The characters seem two-dimensional, especially the males

who mostly range between the self-absorbed husband, the cheating husband, the amorous

lover and the slob of a husband, among others. In comparison, the women mostly

seem to be driven, independent, strong-willed and emotional. The stories seem mostly in favour of the female characters.

Some stories are so ridiculous; they are funny, such as the frizzy-haired wife who discovers Keratin, and that helps her reignite her bedroom antics with her husband, while other stories seem borderline ludicrous, such as the mother-of-two who sleeps with an American at a wedding and he convinces her to move to LA with him.

Though the author is careful to throw in Cairene references like Tivoli and Harris Café, the characters seem to live in another world, one

where kisses can casually be shared in cars, wives can easily sleep with

strangers in Sharm El Sheikh, and turbulent domestic disputes can easily be resolved with a witty one-liner.

The characters’ emotions lack substance, and the author fails to explore certain characters’ moral ambiguity or tap into the complexity of Egyptian society today, where fear of societal repercussion still prevails.

That being said, credit

should be given to the author for avoiding blatant anti-male shtick or preaching against relationships, unlike many of her contemporaries. What Taher

does preach, however, is the need to fight for love, a message that is printed

in her introduction as well as on the back cover.

Taher’s

stories read like fairytales: they lack realism, the characters are either villains or heroes, the dialogues

seem contrived and conflicts are resolved far too easily. While it’s good to

believe in love, the stories she uses to back up her belief may leave some

exasperatedly throwing up their hands in the air and yelling ‘Oh, come on!’

While the author’s writing quality may be

considered high on Egyptian standards; it is comparatively poor in the

Western publishing hemisphere; judging by errors and poor language style in

several parts of the novel. That being said, the book is a commendable debut effort by the author that will hopefully mature and develop in the future.

Write your review

recommended

Cafés

Cafés

Bite Into the Croffle Craze: The Best 5 Spots to Try Croffles in Cairo

cafes cairo +2 City Life

City Life